Institute of Contemporary Arts, London

03 February – 10 April 2016

From the colourful urns of Grayson Perry and the BBC’s new reality series The Great Pottery Throwdown to your favourite café serving up cortados out of a hand spun cup, there is nothing cooler right now than contemporary ceramics. But before there was cool, there was Betty Woodman. 85 years brilliant, the groundbreaking artist is finally receiving the recognition she deserves with her first solo exhibition in the UK. Theatre of the Domestic at the Institute of Contemporary Art in London showcases recent and new mixed media works by the prolific artist. Over the years Woodman has forged a happy marriage between art and craft, boldly collapsing traditional hierarchies to mould our understanding of contemporary ceramic practice.

Whilst she now defies categorisation, a potter, a painter, a sculptor, an installation artist, Betty Woodman was first and foremost a ceramicist. Today her work continues to be informed by the form and iconography of the archetypal ceramic object, the vase. Vases are portrayed in paintings. Paintings are featured on vases. Paintings take shape around and in conversation with actual vases. Paintings become tables for vases. Fragments of deconstructed vases are scattered and composed to form a dance across the gallery wall. Woodman’s playful reinterpretations of the vase come together to act out The Theatre of The Domestic. Once limited to holding flowers or sitting neatly upon a kitchen shelf, the function of the vase is rendered infinite.

Despite these endless possibilities however, the vase, symbolised as vessel, will always carry connotations to the female body, This is embodied in ‘The Kimono Ladies’ in which ceramic vases are loosely draped in fabric to take on the form of women. Painted in an eclectic array of colours and patterns, ‘The Kimono Ladies’ are a playful depiction of women achieved by use of simple shapes and gestures. Woodman doesn’t want audiences to be dazzled and distracted by her craftsmanship (although she does acknowledge that the medium must be mastered before it can be deconstructed). The incorporation of Eastern fabrics is a nod to the Orientalist interests of Modern painters like Matisse.

Woodman’s oeuvre is constructed of many layers of meaning like this, regularly speaking to both the rich history of the vase, and that of Modern art. Theatre of the Domestic also reveals visible references to Japanese screen printing, Roman frescoes, Etruscan pots not to mention other painters such as Picasso, and Bonnard whose work she admits to being “totally besotted” with. Layered with the languages of traditional ceramics and that of Modern painting, Betty Woodman creates her own, new language.

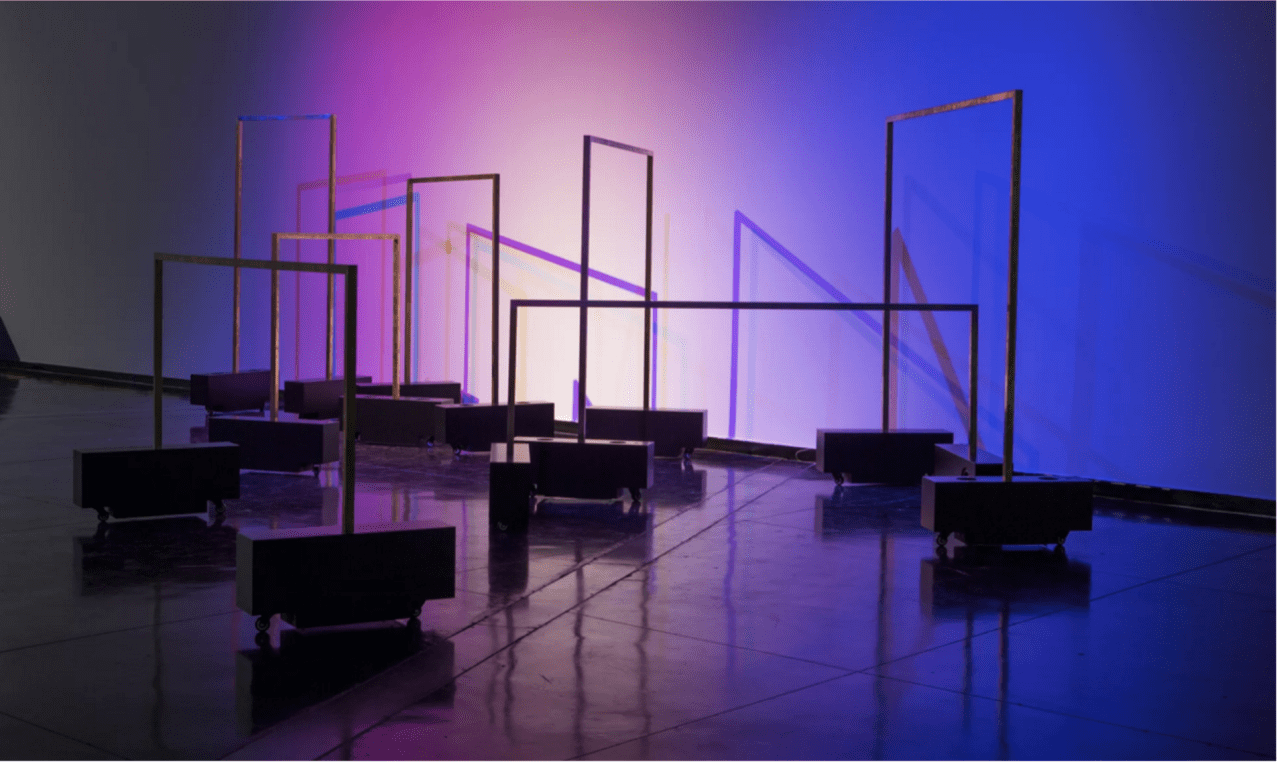

The final act of Theatre of the Domestic reaches a crescendo in the upstairs galleries of the ICA. Comprised of four large canvases, ‘The Summer House’ (2015) stretches across the entire wall of the intimate and rather domestic space. The work depicts a soft and humble interior; a table, topped with ceramic vessels. The artist’s palette is gentle, her brushstrokes, loose and gestural. The distorted perspective of the room invites the viewer to enter the work. However, upon closer inspection, it is visible that the work in fact enters the world of the viewer. The table painted onto the canvas becomes three dimensional, suddenly protruding into the gallery space. It is topped with a series of three dimensional painted ceramic vases, all of which, when at a distance, appear to flatten into the two-dimensional plain of the canvas. The distinction between the world of the painting and the world of the viewer is dismantled and confused.

To the right of the table, two larger urns are positioned on the floor. These are raw and unpainted, the contrast drawing focus to their form. To the left, a third urn is found subtly absorbed by the canvas. This one is painted. In transforming the object of the vase, into the subject of the painting, the domestic world collides with the very constructed, world of “high” art. Although wary of entering the domain of the painter, Woodman wanted to present a new way of looking at painting – and so the three-dimensional ceramic object was added, offering the viewer a different experience from each angle.

Unlike many contemporary artists, Betty Woodman does not shy away from the decorative. A self- proclaimed Formalist, the artist hopes that viewers will take comfort and delight in her work on an aesthetic level. Her practice however, is not solely defined by beauty. Its continuing appeal lay in the work’s ability to be at once decorative and conceptual. Woodman again displays her defiance towards categorisation – demanding, after all, why can’t it be both?

This aesthetic accessibility combined with the familiarity of the vase form, allow for viewers of all walks, to enter into the work. Woodman hopes that, after spending time with her work, viewers will find moments in which to connect with it and develop their own personal understandings. She hopes to invoke a sense of wistful nostalgia. In transforming her practice from that of production ceramicist to contemporary artist, Betty Woodman creates a space for her vases in which people can encounter them and engage in meaningful dialogue.

Whilst it is unusual for the ICA (known as a frontrunner for contemporary culture) to be presenting a UK debut following the artist’s retrospective at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art ten years ago, it is refreshing that such an oversight be acknowledged. Embraced with enthusiasm by the public, Theatre of the Domestic has certainly rectified this. The work of Betty Woodman speaks to audiences both old and new. Layered with references to the history of art and the tradition of ceramics, her work is also playful, happy and alive. As delightful as it is challenging, Woodman’s installations reshape our understanding of what ceramics can be, and as such, what contemporary art can be; conceptually bold and pleasantly refreshing.