Reflections on an evening in Melbourne with Miranda July

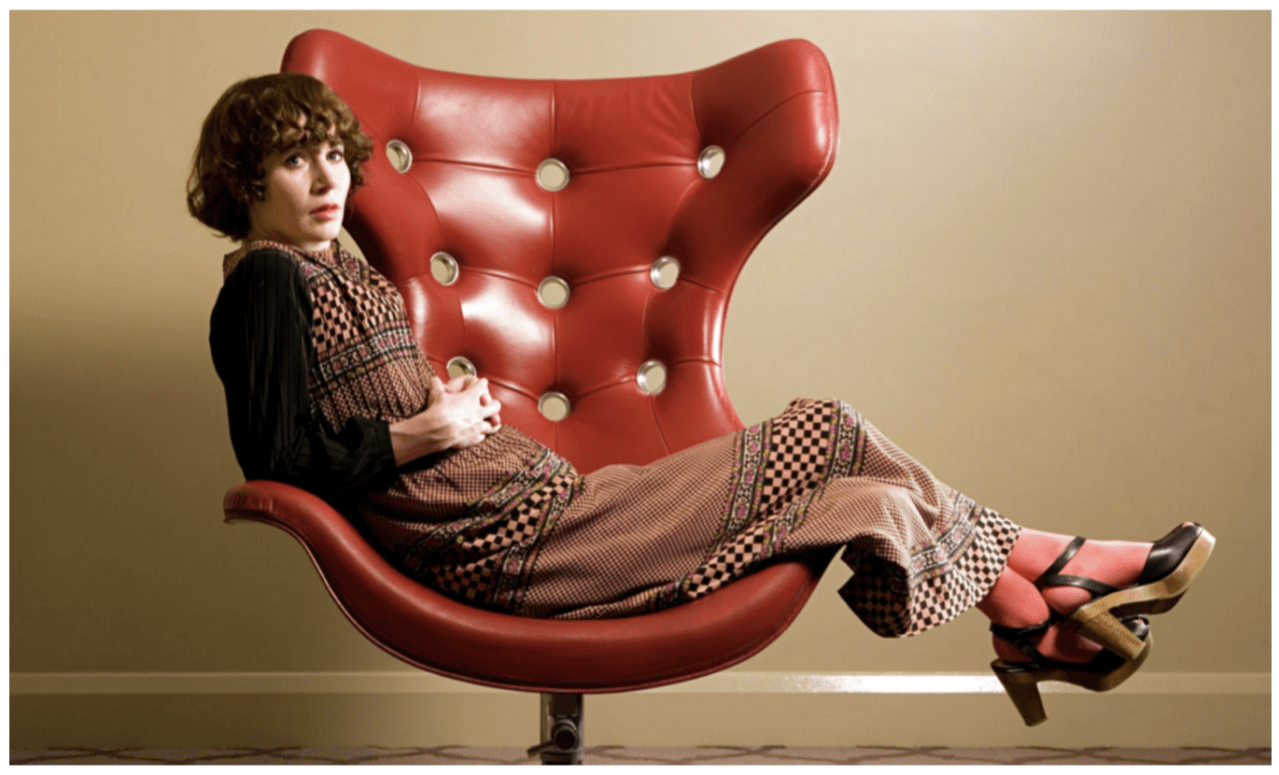

Miranda July | Lost Child!

Melbourne Town Hall | Melbourne, Australia 7 March 2016

Surviving Discomfort. That could have been the tagline for her presentation, ‘Lost Child’, Miranda July told us after she accidentally projected her email inbox in front of a full house of excited admirers at The Melbourne Town Hall on Monday night. The super startist immediately humanised herself. “Close your eyes. No seriously” she awkwardly urged us. It could not have been a more fitting opening to the evening. It was funny, uncomfortable, and real.

What was ‘Lost Child’ anyway? Many of us didn’t even know. It was simply enough that Miranda would be there. Miranda July feels like a friend, and so it is on a first name basis that she will be addressed. We soon learnt that ‘Lost Child’ refers to the title of the first ever book written by Miranda at the age of just 7. She was generous enough to share a few pages of her endearing first ever written work with us. From the short snippet, it was evident that she was a child destined for a bright and quirky future. Throughout the evening that took shape as an autobiographical talk, the audience was offered an intimate insight into this artistic journey and the staggering mind of the artist, delivered via some of her lesser-known works.

Miranda is an artist. I use this term in the loosest way possible, for in fact, Miranda defies the limits of categorisation. Artist, performer, writer, dancer, actor, producer, director… Like most stubbornly independent souls, she refuses to be defined by just one label. She admitted her hesitation to embark on another film after the success of her directorial debut Me and You and Everyone We Know (2005) due to a fear of being categorised as an Indie Filmmaker. As such, she didn’t release a film for another 6 years.

The images, footage and stories selected by Miranda for which to share her early years with us throughout the evening were inconveniently interrupted. A series of slides that revealed a list of banal day jobs worked by the artist to support herself flashed across the screen. Cashier. Cashier. Stripper. Car door unlocker for Pop-a-Lock. These boring black-text-on-white-background slides were supposed to be inconvenient because for a young artist trying to shape her place in the world, these jobs were inconvenient. (The insights offered by the slides remained however fascinating and somewhat entertaining). We were reminded again that Miranda is real. And so was her struggle. Did I mention she was a chronic shoplifter?

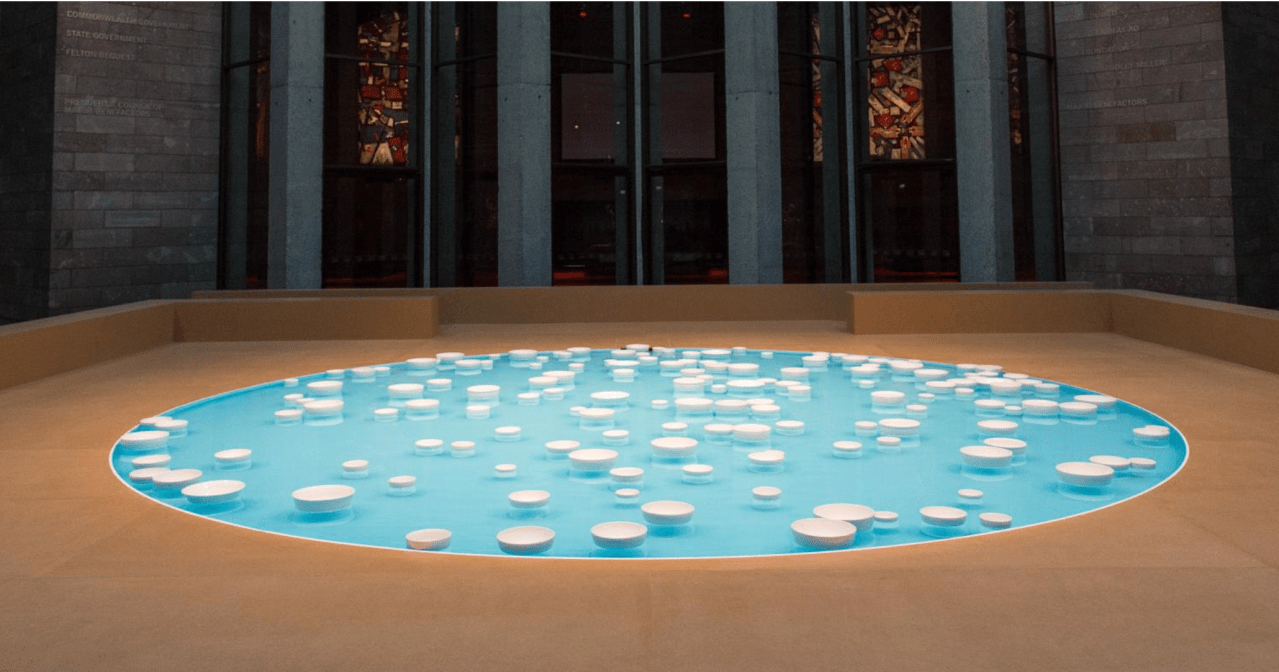

Realness came to embody much of the artist’s work that features everyday people and everyday moments. For real art, to Miranda, was not that which existed in galleries and museums, but belonged to everyday moments that occurred in the real world. Together with Harrell Fletcher, Miranda decided that it was the role of the artist to point out these moments. And thus, as many were still learning what www stood for, Learning To Love You More (2002-2009) was borne. This participatory project used the Internet to facilitate everyday creative experiences, inviting audiences around the world to perform and share their assignments (set by Miranda and Fletcher) with one another. Ironically the project was later acquired by the San Francisco Museum Of Modern Art, however it remains accessible online as an archive.

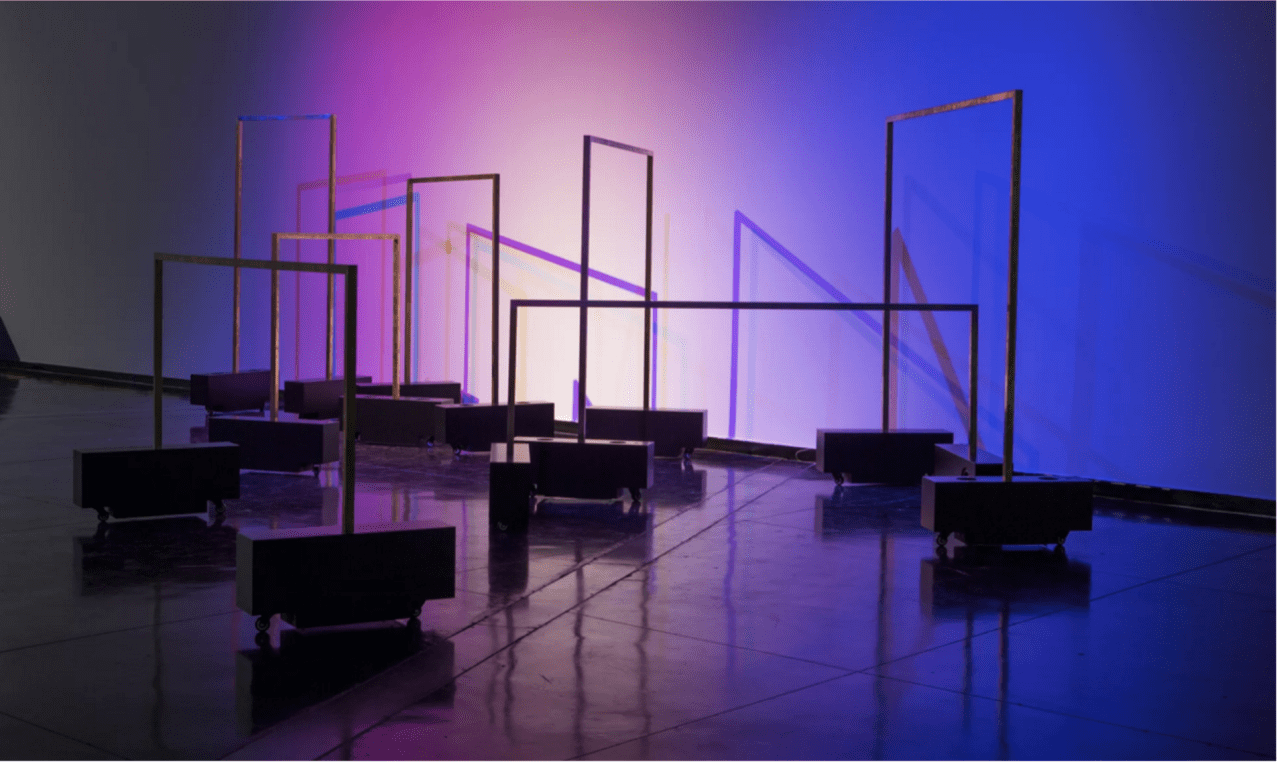

Miranda’s interest in using technology to engage strangers with the outer world through performance was more recently demonstrated by the development of the iOS message delivery application Somebody (2014). When using the app, instead of your message being sent directly to your friend, it would be sent to a nearby Somebody user (most likely a stranger) who would in turn physically deliver/perform that message to the designated recipient.

Miranda’s interest in encounters with strangers and the discomfort this often brings, alongside her belief in a democratic art, has informed much of her work. Amateur strangers have played a central role in many of her productions. From Richard her shoe repair man who featured in a questionable early short film, to a young removalist in LA whose audition tape we were privileged to view, and let’s not forget Joe, an elderly kindred spirit found in the Pennysaver who is featured in the book It Chooses You (2011) and stars in The Future (2011). He plays the Moon. The willingness of strangers to engage in Miranda’s projects, just as we the audience participated in several interactions orchestrated on the evening, demonstrates the artist’s ability to gain our trust. It also suggests our own desire to be a part of something, to feel connected. In a world in which strangers grow increasingly suspicious of one another, we trust Miranda because she is honest, warm and humble. She welcomes us into her world with open arms and thus we feel like old friends.

‘Lost Child’ confirmed what we all already knew about Miranda July. That she is brilliant. More than that, it reminded us that she is real and that her life is just as full of uncertainties as the rest of ours. It is in these moments that we are lucky to have a friend like Miranda to whom we can turn. Her awkward humour, quirky wit and endearing openness help shed light on the art in all of our lives. This is both comforting and inspiring. In ‘Lost Child’, as across her practice, Miranda Jennifer July generously shares her experiences of uncertainty and discomfort, so that we can better survive our own. (She even shared her middle name with us. Yes, Jennifer. And no, she is not thrilled by it. That is real.)

This article was originally published by Art Kollectiv in March 2016.